Despite harsh sanctions, Dutch-made microchips continue to end up in Russia. It involves many millions of pieces from the beginning of the invasion in Ukraine until December.

Exports are routed through intermediaries. Several hundred deliveries have been made to three Russian defence companies. ‘Dutch’ chips were also discovered in Russian weapons.

The NOS and Nieuwsuur investigative editors were given access to trade data, spoke with involved companies, government agencies, experts, and researchers, and were given access to confidential documents. The study provides the first look at the scale at which microchips manufactured in the Netherlands end up in Russia.

There is a clear pattern of a small group of Chinese firms obtaining Dutch chips and exporting them to Russia month after month. One such company is sanctioned by the US for supplying the Russian defence industry. Despite increasingly stringent sanctions, there has been no decline in exports in recent months.

The majority of Dutch chips exported to Russia are produced by major chip manufacturers such as NXP of Eindhoven and Nexperia of Nijmegen. According to the NOS/Nieuwsuur investigation, NXP microchips were recently discovered on the battlefield in Ukraine.

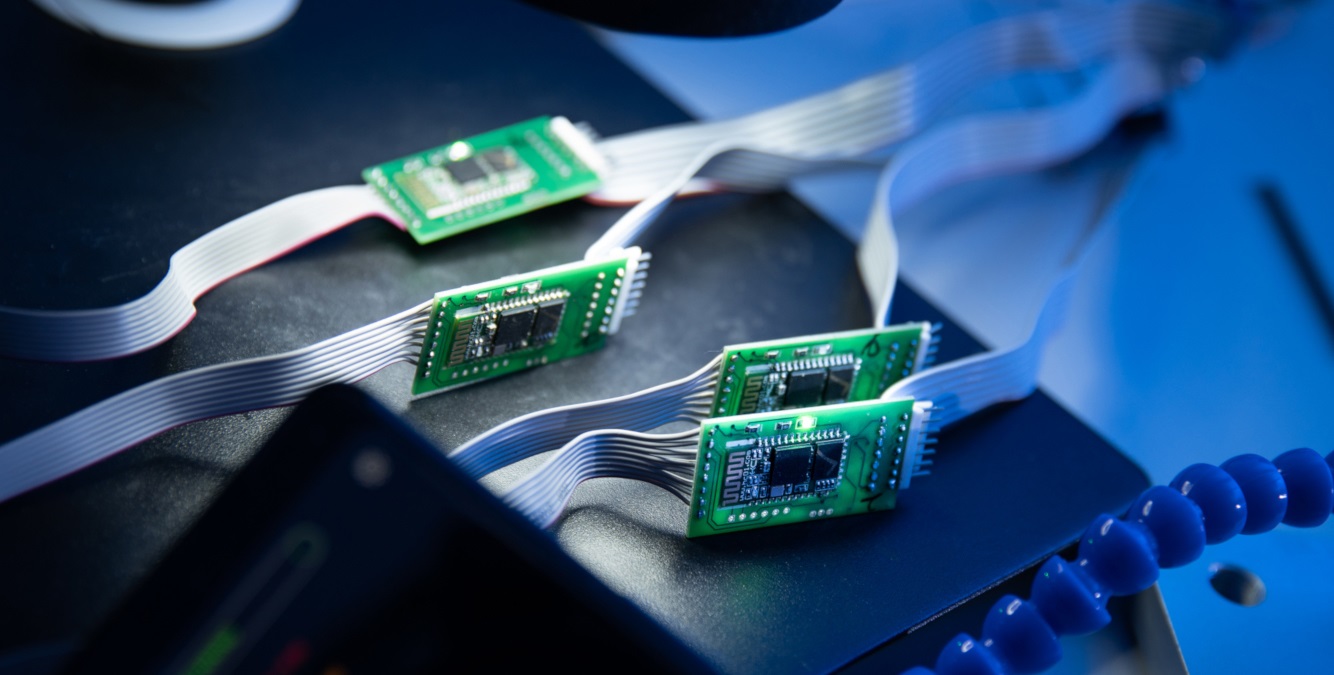

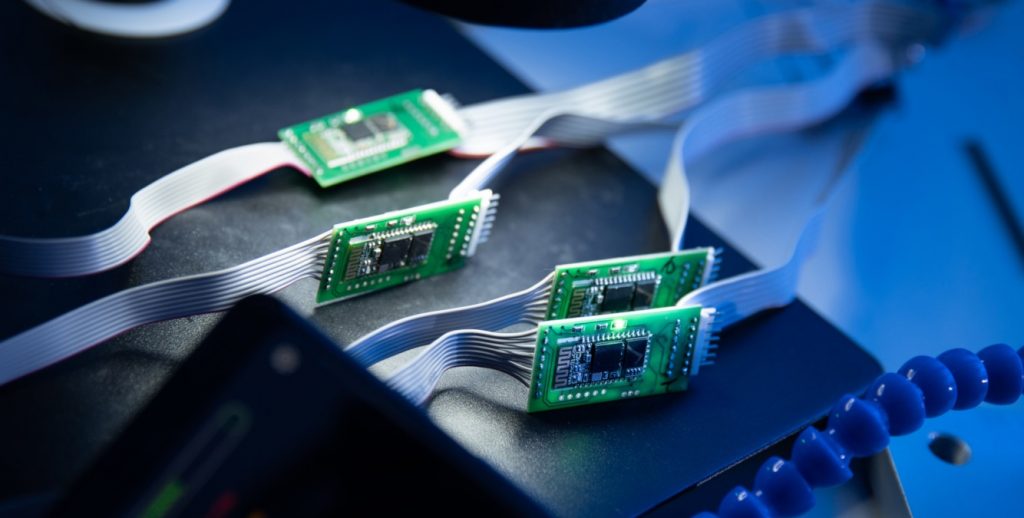

They were discovered in disassembled Russian armoured howitzers, cruise missiles, and attack helicopters, among other places:

Previous research has discovered NXP and Nexperia chips in Russian drones, as well as an NXP chip in an Iranian kamikaze drone. Moscow employs all of these weapons to assassinate Ukrainian soldiers and civilians.

The companies, according to their spokespeople, follow the sanctions rules and do not do business with Russia. Customers are also not permitted to sell chips to Russia. They claim they are powerless if chips, of which NXP and Nexperia produce billions globally each year, end up in Russia via parallel trade.

The producers are required by law to conduct “due diligence” in order to prevent their chips from being sold to Russia. Dutch producers claim to do the same. According to experts, while this so-called due diligence provides guidelines, the EU guidelines do not include any legal obligations.

The two multinationals say they have no idea how the same rogue middlemen continue to buy chips. NXP customers are being screened “vigorously,” according to the company’s response. In terms of sanction compliance, the company claims to go above and beyond legal requirements. It is unclear what this means and whether the company will take action against the group of Chinese middlemen.

Nexperia insists that its export control team uses the latest software “to monitor our distribution”. If a distributor has violated the sanctions, the contract will be terminated. Whether this happened last year, the company does not want to say. Bottom line, resale to third parties “cannot always be controlled or prevented by us”.

Major concerns

According to the government, the shadowy brokering of microchips occurs without the permission or knowledge of Dutch manufacturers, according to a response from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“The Netherlands is very concerned about this and, together with the European Union and other EU countries, is looking for effective ways to prevent this and to tackle brokering.”

In addition, an even larger flow of microchips manufactured outside of the Netherlands ends up with Russian importers. There are at least 2 million chips distributed across dozens of companies in November alone. In comparison, over 60,000 chips were produced from NXP and Nexperia factories during the same time period, accounting for approximately 6% of the total.

Experts believe that the Russian import flow is continuing and that there is no evidence that it has ceased. However, no trading data for January is yet available.

It is impossible to say how much of the recent supply of chips ends up in Russian military equipment and how much ends up in washing machines, telephones, or other consumer products, for example.

“A range of Dutch components are crucial to the Russian war machine,” said James Byrne, director of the Open-Source Intelligence and Analysis Research team at the British think tank RUSI.

“These chips are regularly found in almost all types of Russian military drones and other precision weapons, such as cruise missiles.” NXP chips were found in 10 of the 27 Russian weapon systems that RUSI examined at the request of Ukraine, the institute reported last summer.

Circumventing Sanctions

EU sanctions against Russia are routinely flouted. Small businesses, for example, that ship chips to Russia via parcel post. There are also mostly Asian traders who buy Dutch chips and resell them to Russia at high profit margins, unhindered by sanctions.

According to data available to NOS and Nieuwsuur, China-based Sinno Electronics is the largest intermediary trader in Dutch chips. However, unlike Washington, Brussels has not yet imposed sanctions on Sinno. The company was contacted for comment but did not respond.

When asked why these, or any intermediaries for chips to Russia at all, have been put on the EU sanctions list, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs says: “The Netherlands does not make any statements about concrete proposals for new sanctions, so as not to undermine the surprise effect and thus the effectiveness of measures. to undermine.” Consensus within the member states is also needed to sanction a company, they add.

Control is ineffective due to the significant role played by Chinese exporters in particular. Because Beijing has not imposed any sanctions on Moscow, trade in Chinese chips is still possible. As a result, the NOS/Nieuwsuur study indicates that very limited intervention was possible in the past.

The Public Prosecution Service is currently dealing with one criminal prosecution. According to Customs, tens of thousands of checks have been performed. In the case of microchips, this ultimately resulted in the blocking of one cargo worth 300,000 euros.

“To date, we see that prosecution of sanctions violations is mainly limited to ‘indeeds'”, said sanctions lawyer Yvo Amar. He estimates that in fifteen years there have been only ten convictions, in which complicated trade constructions via third countries remained unaffected. According to Amar, “serious work” is now being done, but it remains difficult and very time-consuming for the judiciary to also bring more complex cases to court.

“I do think that companies can still do more than they are doing at the moment,” said Amar. Case in point, chipmakers can contractually stipulate that an importer in China, for example, can be checked for what a chip has ultimately been used for, or has been resold.