The longstanding trade relationship between Africa and Europe, two geographical neighbors, is currently in a state of confusion. The European Union’s (EU) fragmented trade agreements across Africa are causing a balkanizing effect, just as African nations are striving for economic integration through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). A new edited volume suggests that aligning these divergent trade policy priorities necessitates a reset.

The EU is Africa’s primary trading partner, accounting for 26% of all imports into African countries in terms of value, followed by China (16%), and intra-African imports (15%), based on IMF data from 2018 to 2020. Other partners like the US (5%) and the UK (2%) are significant but less so.

The pattern of Africa’s exports closely mirrors its imports, with the EU being the most important destination, accounting for 26% of all African exports in terms of value. Intra-African exports (18%) and China (15%) follow suit. India (6%), the US (5%), Turkey, Brazil, UK, Japan, and Russia (each under 3%) are smaller export destinations.

The EU’s imports from Africa primarily consist of fossil fuels (40.7%) and other primary commodities such as ores, metals, and other minerals (14.2%), as well as food items (15.7%). This reflects Africa’s weak industrial base, which has remained unchanged for decades. Conversely, manufactured goods dominate Africa’s imports from the EU.

The EU is also Africa’s most significant investor, with investments primarily concentrated in the mining sector, including fossil fuels. Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, and South Africa are exceptions to some extent due to more diversified trade resulting from substantial European investment in non-extractive sectors.

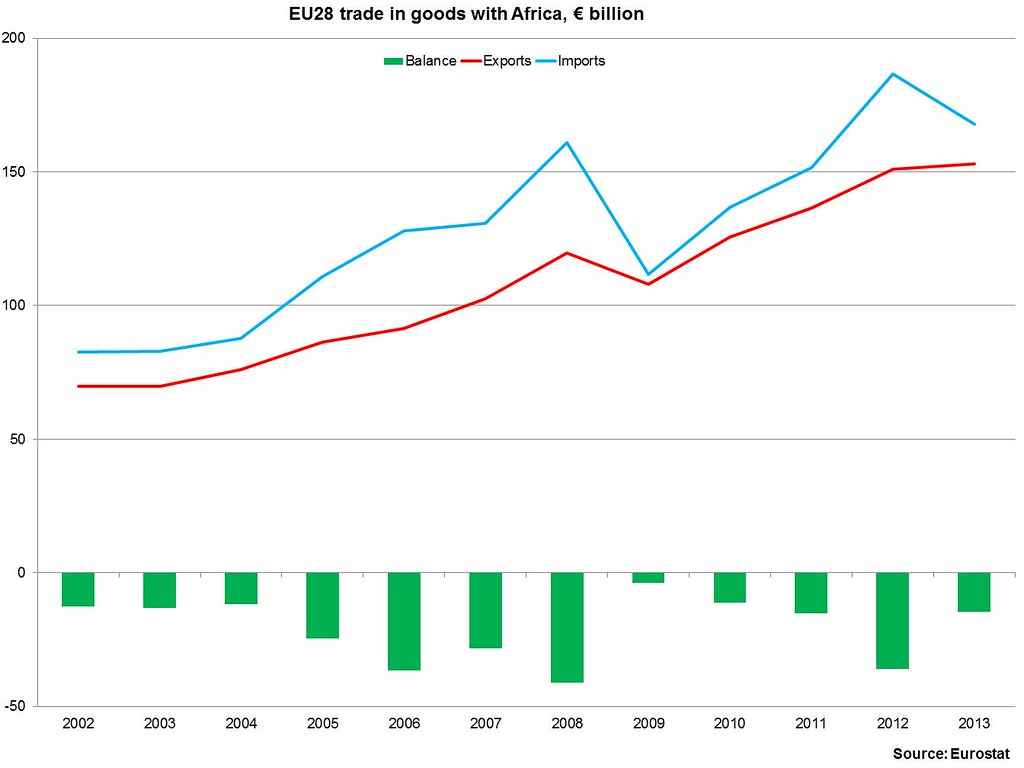

Africa’s trade relationship with Europe is highly asymmetrical and has been since the independence era in the 1960s. This pattern is also seen in Africa’s trade with partners like China, the US, the UK, and emerging economies like India and Turkey. However, the EU has a greater economic gravity that can significantly influence how trade emerges as a development lever in African countries.

Despite being home to around 17% of the world’s population, Africa accounts for just 2.3% of world trade and only 3% of global GDP. The continent also accounts for just 2% of the EU’s trade. This creates an unbalanced playing field where the EU’s trade policy decisions significantly impact Africa, but Africa’s decisions matter relatively little to the EU.

Intra-African trade, which represents 15% of Africa’s trade, tends to be more diversified and higher in value-added content than Africa’s exports to external trading partners. Manufactures constitute the largest type of export within the continent, accounting for 45% of all formal intra-African trade. Food exports also play a significant role, making up a fifth of trade between African countries. However, these ‘formal’ figures do not capture much of Africa’s trade that occurs informally across contiguous borders and goes unrecorded. Recent estimates suggest that such informal trade flows account for between 7 and 16 percent of formal intra-African trade flows.

Africa’s trade with the EU (and other partners) exhibits two distinct patterns. The first is a pattern of commodity concentration in Africa’s exports to the EU and the rest of the world. The second is a pattern of greater diversification when Africa trades within itself. This second pattern offers a viable pathway for Africa to utilize trade as a meaningful tool. Intra-African trade and economic integration could pave the way for industrial development and transformation in Africa, leading to more meaningful trade with the EU and the rest of the world.

However, European trade policy towards Africa is inconsistent with its publicly stated intention to support AfCFTA-led integration of the African continent. Specifically, the EU’s fragmented trade regimes result in hard borders for EU trade between African countries within the same regional customs union. It is challenging to envision how a continental customs union could emerge from the divisions created by the EU. Consequently, African and EU trade policy priorities are in disarray.

The solution suggests strategic sequencing of AfCFTA implementation before reciprocal opening to the EU. Empirical evidence from the Economic Commission for Africa based on economic modeling for trade in goods found that implementing the EU reciprocal agreements ahead of the AfCFTA would result in losses in trade – or trade diversion – between African countries.

Conversely, if the AfCFTA was fully implemented before the reciprocal agreements, this negative impact would be mitigated. Trade gains by both African countries and the EU would be preserved, while intra-African trade would expand significantly benefitting trade in industrial goods. Further evidence from ECA modeling results which took liberalisation of trade in goods and services along with reduction of non-tariff measures into account affirms the need for correct sequencing. This study found that the current share of intra-African trade would nearly double following the AfCFTA reforms. Most of the gains will accrue to the industrial and agrifood sectors as well as services, which are critical for Africa’s transformation.

To untangle the current trade policy confusion, it would be beneficial for the EU to provide all African countries with unilateral market access that is duty-free and quota-free, along with a unified rules of origin regime for a transitional period. This period should be benchmarked against milestones in AfCFTA implementation and the emerging gains from it. Such a move would require multilateral legitimisation through a World Trade Organization (WTO) waiver.

It’s important to acknowledge that the WTO’s ‘one size fits all’ rules need to be reimagined to address the realities and challenges of the 21st century faced by late developers, such as African countries. The precedent set by the United States’ African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) in obtaining a WTO waiver for non-reciprocal trade concessions suggests that this should not be an insurmountable task.

Given that Africa, as the world’s least developed continent, accounts for only 2.3% of world exports, concessions to Africa pose no threat to the international trading system. Allowing non-reciprocal access to advanced country markets for a transitional period is strongly pro-development. It encourages African countries to seek trade opportunities with each other and mitigates the risks of trade diversion.

By ensuring the right sequencing for the AfCFTA, this approach will also help Africa build productive capacities and achieve its potential for strong and diversified growth in intra-African trade with inclusive and transformational consequences. It has the potential to change the record of the last 60 years, during which the structure of Africa’s external trade has remained unchanged.